Georgius Gemistus (later called Plethon), was one of the most renowned philosophers of the late Byzantine era. He was an important pioneer of the revival of Greek scholarship in Western Europe and re-introduced Plato's ideas to Italy during the 1438-1439 Council of Florence. His great literary work, the Nomoi or Book of Laws, which he only circulated among close friends, made a rejection of Christianity in favour of a return to ancient wisdom based on Pagan Greek philosophy and Zoroaster. He adopted the name Plethon out of his deep admiration for Plato's philosophy. Cardinal Bessarion once speculated as to whether Plato's soul occupied Plethon's body.

Plethon was born in Constantinople around 1355AD. Raised in a family of well-educated Christians, he studied in Constantinople and Ottoman Adrianople, before returning to Constantinople and establishing himself as a teacher of philosophy. He also served as a senator in Constantinople and a judge. Eventually, in about 1410, he was sent to Mystras by Emperor Manuel II. At Mystras he established something of an academy, perhaps modeled on his beloved Plato. A great many of the most famous 15th century Greek humanists were at one time or other his pupil.

When Emperor John VIII departed for Italy to seek Western Christian aid against the Turks, he included Plethon in the delegation, despite his being a secular philosopher, on the basis of his renowned wisdom and morality. Other delegates included Plethon's former students Bessarion, Mark Eugenikos and Gennadios. He was not included in the Council's religious debates and instead, at the invitation of some Florentine humanists, he set up a temporary school in Florence to lecture on the difference between Plato and Aristotle. According to Marsilio Ficino, Cosimo de Medici was among those who attended and became subsequently enthralled by Plato.

While still in Florence, Plethon wrote a volume titled Wherein Aristotle disagrees with Plato, (De Differentiis), to correct the misunderstandings he had encountered. He claimed he had written it 'without serious intent' while incapacitated through illness, 'to comfort myself and to please those who are dedicated to Plato.' Gennadios responded with a Defence of Aristotle, which elicited Plethon's subsequent Reply.

This Reply letter is not a sober academic piece but a work of venomous personal invective directed at Gennadios:

"Along with your other faults, lying comes naturally to you. . . .

You are not only vindictive, but dull-witted, as your present work shows . .

. . . a man who has no shame in boasting about the influence of a wretched woman -- and a little tart at that . .

You seem to be so consumed with your vanity that you will even sacrifice your religious beliefs for it, changing them at every opportunity in whatever direction you think will bring you greater esteem. . .

They are certainly not stupider than you, for it would be hard to find among serious students of Aristotle anyone stupider than you. . .

You can have nothing to say that affects me . . . I have paid, and shall continue to pay, no more attention to it than to the howling of a Maltese whelp. "

He seems to have been an old man full of bones piss and vinegar and very definitely not someone, as Anna knew, one invites on a picnic if one requires only flattery.

Still, clearly Plethon could be a charming, loveable man as well. That aspect of his character comes through in the monody he wrote for the funeral of Cleofe Malatesta, the wife of Theodoros Palaiologos, the Despot of Morea. Gennadios aside, most of those around him appear to have treasured him greatly.

"Along with your other faults, lying comes naturally to you. . . .

You are not only vindictive, but dull-witted, as your present work shows . .

. . . a man who has no shame in boasting about the influence of a wretched woman -- and a little tart at that . .

You seem to be so consumed with your vanity that you will even sacrifice your religious beliefs for it, changing them at every opportunity in whatever direction you think will bring you greater esteem. . .

They are certainly not stupider than you, for it would be hard to find among serious students of Aristotle anyone stupider than you. . .

You can have nothing to say that affects me . . . I have paid, and shall continue to pay, no more attention to it than to the howling of a Maltese whelp. "

He seems to have been an old man full of bones piss and vinegar and very definitely not someone, as Anna knew, one invites on a picnic if one requires only flattery.

Still, clearly Plethon could be a charming, loveable man as well. That aspect of his character comes through in the monody he wrote for the funeral of Cleofe Malatesta, the wife of Theodoros Palaiologos, the Despot of Morea. Gennadios aside, most of those around him appear to have treasured him greatly.

Gennadios was to get the last laugh in that bitter rivalry of master and rejected pupil. In 1460, when the Morea fell to the Ottomans and Theodoros's young brother, Demetrios, was summoned to Adrianople with his wife Theodora, they stopped at Serres, where the now ex-Patriarch, Gennadios, was living in monastic seclusion on nearby Mt. Menoikeon. The manuscript of Plethon's great work, "Laws" appears to have been among their possessions and Theodora - a devout woman, likely troubled by the overt paganism extolled in the work - handed it over to Gennadios.

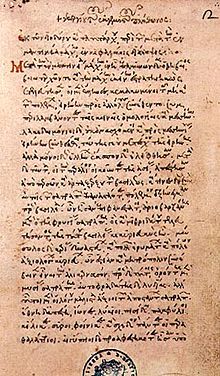

Gennadios read the work, a tremendously upsetting experience he claims, that brought him to tears. He made a list of chapter headings and a summary then sent the book back to Theodora, with instructions to burn it. She couldn't bring herself to do so and sent the book back to Gennadios who burned it himself, in a public ceremony. It was possibly the only copy in existence.

Gennadios was found of burnings. A few years before this he had sent a letter to the Morea vividly describing how a heretic should be tortured and then burned. I was perhaps unfair to the man to portray him as I did in Porphyry and Ash, but then again, perhaps not.

Still, Plethon was not above burning people either. In the Laws he recommended it as punishment for those guilty of perversions of sexuality (which he considered divine). These perversions included bestiality, pederasty, rape, incest, and male adultery. Notice, however, these did not include homosexuality as a perversion.

Plethon's writing is full of a sense of physical knowledge. In a society that appears to have been quite awkward and sexually repressed (Cleofe Malatesta and her husband took six years to consummate their marriage), Plethon was anything but.

"Desire is a gift of the gods," he wrote. It is the way we approach the gods since it is a thing most beautiful and most divine to marry and have children. We cannot deny the importance of this act which in our mortal nature is the imitation of the immortality of the gods. We ought to see that we do it well. We do this in private not because of shame, but because most humans do not wish to display publicly those religious acts which they regard as the most holy. It is the most personal thing people can do, and since it is one of the most important things given to people to do, it deserves to be done as perfectly as possible. Nothing is more shameful than an important act poorly done.

Plethon himself had two children, Demetrios and Andronikos. Both were alive and of age in 1450.

There is disagreement over when precisely Plethon died. Some say 1454, others 1452. Hence I have felt comfortable splitting the difference at 1453 to suit my purposes. He would have been in his nineties in any event. In all probability he died peacefully in the Morea and we might hope it was the earlier date to prevent him learning of the cataclysmic fall of the capital and the death of his old pupil Constantine.

In 1464, another Malatesta came to Mystras. Unlike Cleofe, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta was not well loved and did not come to marry into the dynasty. A famous Italian Condottiero, Malasesta had been hired to lead Venice's land forces in their campaign to drive the Turks out of southern Greece. It proved an unsuccessful venture, but Malatesta was able to pull off one personal coup. A true renaissance man, Malatesta was an admirer of Plethon and returned to Rimini where he was funding the reconstruction of the Tempio Malatestiano, as a personal mausoleum. Malatesta wanted to include the tombs of illustrious people and so had the bones of Plethon dug up and brought back to Rimini with him, where they remain within the side chapel.

Readers of Porphyry and Ash might find this difficult to imagine since my version of history does not seem to allow for Plethon's bones to be in Mystras. For this, we might consider two possible explanations.

The first is that Malatesta dug up any old bones and made up the story to add provenance to them and secure something from an otherwise dismal campaign. The third is that faced with an armed general demanding to know where the grave of a philosopher was, some enterprising peasant showed him any old tomb and let him dig it up. Note I am not arguing this is actually what happened - probably Plethon remained in Mystras and never returned to Constantinople - I am merely suggesting that Malatesta's story is not necessarily proof that Plethon could not have done.